Following the overview, in this post I want to talk about:

- Tools I used

- Some research I did before starting coding

Tools

Developing environment

I’m using Windows 10, Microsoft Edge and Visual Studio Code

Android devices

I have a Onyx Nova Pro (Android 6), a Huawei Mate 9 (Android 9) and a Samsung Galaxy S9 (Android 10) for testing.

ADB source code

Because ADB is open-sourced and my project will also be, I can refer to it’s source code for help.

The Git repository can be checked out from https://android.googlesource.com/platform/system/core.git (or the GitHub mirror https://github.com/aosp-mirror/platform_system_core).The source code has been moved to https://android.googlesource.com/platform/packages/modules/adb

ADB related files are in the

adbfolder.ADB pre-built executable

Because building ADB is very complicate (you need to build the whole Android system, requiring hundreds of gigabytes of hard drive space and all the configuring), it’s easier just downloading a pre-built binary from https://developer.android.com/studio/releases/platform-tools.

Hack ADB

After a quick scan of the code, I discovered some features that can make my work easier.

ADB_TRACE environment variable

ADB can dump all messages to the terminal, so I can gather real data to test against my implementation.

Set ADB_TRACE environment variable to all enables all debug output, including message dumps.

Run ADB server manually

Set ADB_TRACE alone is not enough. ADB has three parts: ADB daemon, ADB server and ADB client.

1 | +-----------------------------------+ |

Normally, running an adb command will start a ADB client. The client will try to connect to a server running locally, and if there isn’t one, spawn a new one in background.

The problem is that what I want to do is dumping messages between server and daemon, and since the server was started by client in background, there is no way to access its output.

So we need a way to start a server manually. --help message isn’t always that helpful, however I found the answer from source code:

1 | adb server nodaemon |

ADB_EMU environment variable

Upon launching, ADB server will scan through TCP ports 5554 to 5570 on localhost to detect running Android emulators.

With ADB_TRACE=all set, this process results in dozens of connection error messages.

Set ADB_EMU=0 disables emulator detection entirely. While set ADB_EMU={port} let ADB to only search for emulators at {port}.

Logs are … truncated …

After setting these environment variables, ADB now starts outputting messages to the terminal.

1 | adb.exe D 09-28 13:34:34 15484 2084 transport.cpp:687] 5541494e4c583398: from remote: [AUTH] arg0=1 arg1=0 (len=20) 8f402a7b9b59006202c4049f8066f041 .@*{.Y.b.....f.A [truncated] |

However, ADB only prints first 16 bytes, that’s not very useful if we want to see how the protocol work.

Search for code

A quick search leads to adb_utils.cpp#L162

1 | std::string dump_hex(const void* data, size_t byte_count) { |

Sadly the limit is hard-coded and I can’t modify the source code (that requires a rebuild).

Evil method

So I got my Ghidra out. It’s one of the most powerful disassembly tools.

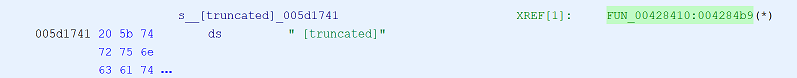

Search for some keywords.

![Search -> Program Text -> " [truncated]"](/blog/2020/09/29/webadb-part1-preparation/search.png)

Double click on XREF to jump to usage.

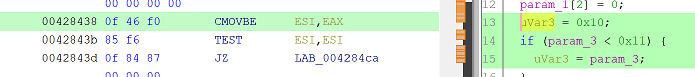

The “Decompile” view shows the reconstructed C code from assembly (I added some blank lines and comments).

1 | // std::string dump_hex(uint8_t* data, uint32_t data_length) |

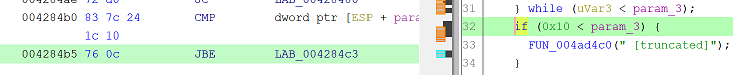

Clearly the target is removing checks at line 19 and 64.

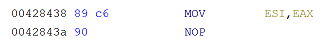

Line 19 is a CMOVBE (Conditional MOVe if Below or Equal), change to a MOV (pad with a NOP).

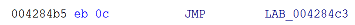

Line 64 is a JBE (Jump if Below or Equal), change to a JMP.

All done. Use File -> Export Program to save a copy, name it adb.2.exe.

Done

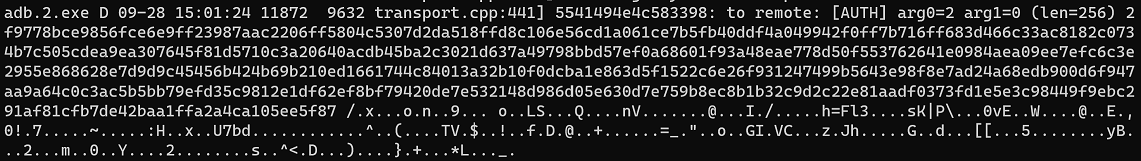

Execute, now it correctly dumps the entire message, so I can observe the compare my implementation with these real messages.

What’s next

Next time I will start talking about the ADB protocol, and my implementation.